The Emperor’s New Clothes might not be for emperors – meaning, the moral of the story might not necessarily be for leaders. Or for tailors, for that matter.

Sure, say you’re a newly-crowned leader and you wish to learn more about running a kingdom, a business, or a team. Perhaps you can learn to not be too greedy. You can also to learn how to smell a con man a mile away. Or you can also learn how not to surround yourselves only with Yes-Men who seem to care about you but actually care only about themselves.

The story might not also be a moralist warning against hackjobs. In fact, there seems to be no admonition in the story for him. He seems to be an accepted part of reality, so this probably tells us that he is a literary mechanism to expose everyone else in the kingdom.

The lessons seem to be for the “people” – the followers in the kingdom. We can sub-divide the people of the kingdom into three. And here, let me allegorize.

First, the “officials” – not quite the emperor, but not quite the “masses.” Yet they are there, somewhere in between, most probably to act as some sort of intermediary. They probably help the emperor find out what the people truly desire, and they help the emperor enact the laws of the land for the good of the people. In the story, they do neither. They keep the emperor in a bubble of the lies he tells himself. Actually, the story could have ended if just one of them did their jobs and pointed out the trick being played on them – but that wouldn’t have been fun for readers, right? They all went along – for fear of being called stupid, for fear that the emperor might think they’re stupid, or just because the status quo was too comfortable for them.

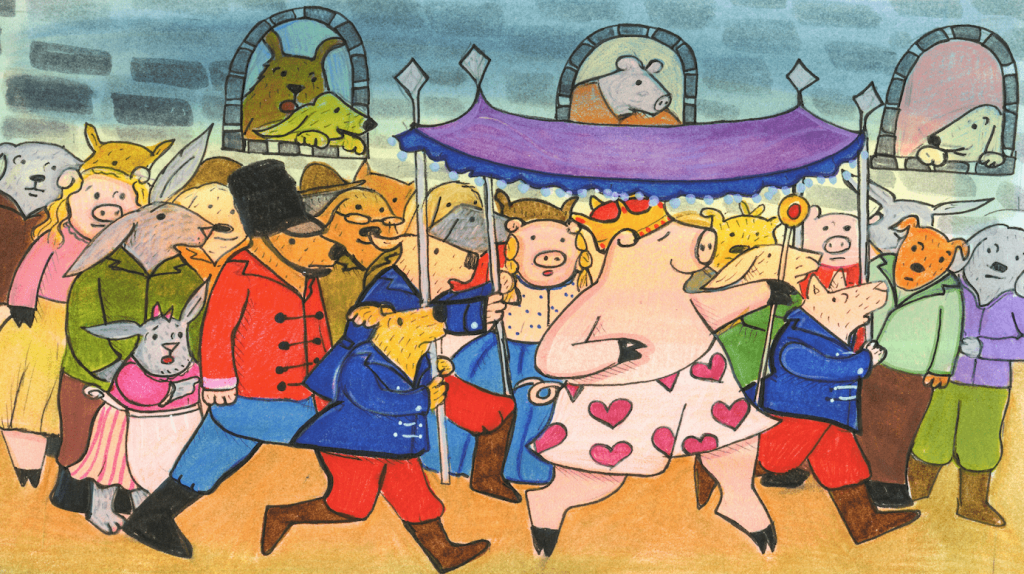

Second, the throng of people in the streets. They meet the emperor in the grand parade. The rumours must have already been flying about the brilliant, dazzling new clothes he was to wear — but only those who are gifted with some sort of ability could see it. The Emperor struts down the street – and well, no one dares to speak the truth. More importantly, no one dares to accept the truth for what it was – their Emperor had been conned, and everyone else accepting the false narrative as well. They wanted to be perceived as “smart” and no, their neighbor isn’t more blessed to see something they can’t, and gosh, they wouldn’t stand for being called “dull” by anyone on their block. The tailor knew what he was doing. What do you do when something is just so plain dumb when you see it in the light of day? Say that only those blessed with holy insight could see what’s going on.

Third, the boy in the crowd. Thank God for him, right? The metaphor can go a bit biblical, in the sense that we were warned by Jesus Himself in Scriptures, that we need a child’s perspective to perceive and hold on to what truly matters. Yet even if you don’t go biblical, there is something to learn from the innocence of seeing something in broad daylight, calling the proverbial spade a spade, and how that clears through the clutter of deceit posturing as truth.

Perhaps when Andersen wrote the story, he wanted us to imagine the Emperor, the conversations between himself and the tailor, the fittings, and the instances when the Emperor looks at the mirror, then judge for ourselves if he was indeed wearing anything. Then he gives us three chances to call the BS out: as a minister, as part of the crowd, and as the child. We probably find ourselves having one of those three opportunities: sometimes we find ourselves in rooms where decisions are made, or sometimes we’re viewing things as bystanders and we just want to get the day done without having to fight on social media about who’s dumb and who’s not, and sometimes we’re the child in the sense that we see wrong plain as day and we just have to blurt it out.

In today’s landscape, it might not be too far-fetched to think that we have too many Emperors on the loose: Emperors who seem to be only caring about the cosmetic and looking only at their mirrors and expecting those around them to be mirrors as well. Amoral hackjobs on sale for the highest bidder are also on the prowl, preying on Emperors’ arrogance and people’s innermost desires.

But they are given realities, it seems. They’re now part of the backdrop of the play. The lines that have to come next must come from the people: whether from those in “rooms where it happens,” from crowds where meaning is manufactured, or from those who can call evil out without fear. The lesson of the story, more than ever, is for us as a people.

Of course in the story, truth triumphs. Because people immediately see the folly. They believe the child. The emperor even goes away in embarrassment – or one might even be so bold as to stretch it to repentance. One can also imagine how he admonishes and fires all his advisers afterward.

But reality tells us the road back to sanity is harder than it seems. It may seem like there are already ten thousand children pointing out con-jobs in broad daylight. Yet crowds push back, our neighbors cover their ears and eyes and mouths, and advisers keep Emperors in bubbles because the status quo benefits them. Yet the timeless story reminds us of the even more timeless adage, that the Truth is what sets us free. And we must keep finding it, pointing it out, fighting for it, and fighting for those who keep calling it out as well.

The Emperor doesn’t need new clothes. The people need new eyes, ears, and mouths.